The U.S. birth rate began dropping years before the pandemic. Heres why

For the sixth year in a row, Americans had fewer children, and births in the U.S. decreased by 4 percent compared to 2019. The new numbers released by the CDC last Wednesday signaled the continuation of a trend that first began following the 2008 recession and has drawn the attention of many demographers and economists in years since.

Despite talk of a possible COVID-19 “baby boom” at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, births declined by about 8 percent from the previous year in December, nine months after the pandemic began.

READ MORE: It’s time to recognize the damage of childbirth, doctors and mothers say

Economists Phillip Levine and Melissa Kearney previously predicted that a “baby bust,” driven by the dual economic and public health crises of the past year, would occur in 2021, forecasting that some 300,000 fewer children would be born next year. Levine told the PBS NewsHour that the decline in births is indicative of a “much larger childbearing problem” going on in the U.S. that is likely to extend well beyond the pandemic. “In the long-term, COVID is going to be a blip,” in this much broader cycle, he said.

But for families who were deciding whether or not to have children over the past year, the coronavirus pandemic felt like more than a blip, and uncertainty surrounding the economy as well as conditions in hospitals spurred many Americans to put off starting or expanding their families.

Even as the U.S. economy turns a corner, several women told the PBS NewsHour that the pandemic exacerbated already-existing anxieties they had about raising children in America, and they’re not certain when they’ll feel equipped to support a family.

“A baby would be a joy in our life,” said Lyssa Uchida, a massage therapist who was out of work for a number of months during the pandemic. “But at 35, I don’t know how much time I have, and I don’t know how much faith I have in being able to provide just basics for a child with what we make.”

‘I’m now more in debt than I ever was’

Even before the pandemic began, millennials had accumulated $1 trillion in debt, according to the New York Federal Reserve, and women held nearly two-thirds of the nation’s student loan debt. For Americans who were already saddled with debt, the most recent economic crisis further decimated their savings and made it harder to consider having children.

“I already have a significant loan from college I’m trying to pay off, and retirement,” said Uchida, who works in Redondo Beach, California. When Los Angeles initially shut down in March of last year, Uchida had to close her studio and could not see clients in person for several months. She received an Economic Injury Disaster Loan from the federal government to keep her business going, but she’ll have to start paying it off in a year.

“That’s going to put me in a hole,” Uchida said of the most recent loan. “I’m now more in debt than I ever was … The idea of having kids doesn’t feel feasible in Los Angeles.”

Uchida said that while she’s trying to come to terms with living a child-free life, she struggles with feeling like she and her husband need to pass on their family legacy through a child. “Part of it is that we’re an inter-racial couple. My husband is Japanese, and I’m caucasian. I feel pressure because of what his family has gone through,” she said, adding that her husband’s grandfather spent time in a Japanese internment camp as part of the Roosevelt administration’s campaign of forced relocation and incarceration during World War II.

“Once you decide that you’re ready to start a family, it feels like any delay in that is just heartbreaking.”At the same time, Uchida said that her parents and in-laws are in their 70s and 80s, and she worries about supporting them while raising children. “When we think about having a child, it’s not just how expensive it would be, but we also have aging parents. We want to take care of our parents,” she said.

Carrie, a 31-year-old woman working in mental health policy research, also encountered financial difficulties while trying to plan for a family during the pandemic. She requested her name be changed because she does not feel comfortable sharing her story on a platform that’s visible to friends and employers.

Before the pandemic, she and her husband, who live outside of Philadelphia, had been planning to start a family and hoped to eventually have three children. But her husband was laid off this past January from his job working for a brewery, plunging the couple into “uncertainty about his career and our financial situation.” While they had initially delayed trying to get pregnant for fear of health complications that could arise from COVID-19, her husband’s layoff prompted the couple to delay children further while he looks for another job in the hospitality industry.

“Once you and your [partner] decide that you’re ready to start a family, it feels like any delay in that is just heartbreaking,” she said. She expressed fears that her “internal clock is ticking,” and that once she did have children, it could negatively affect her professional life.

“It’s a hard balance and the reality is, in your mid-30s, you’re at a point when you’re trying to grow your career and it’s hard to grow a career when you’re planning on having three kids over the next five years.”

Michelle Holder, a professor of economics at New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said that for working women who already have children, the pandemic made it harder to balance child care with their careers, let alone consider expanding their families. 2.5 million women left the labor force between February 2020 and this past January compared to 1.8 million men, and these women were disproportionately Black and Latina. Holder said this could have a “dampening effect” on women’s wages in the future. “If you are for whatever reason voluntarily choosing to leave employment, this has implications for your attractiveness in terms of job candidacy,” she said.

WATCH: Some parents may be pushed out of the workforce due to lack of child care

Holder added that Black women, in particular, face a number of economic challenges that likely made it harder to consider having children last year. According to the National Partnership For Women & Families, 80 percent of Black mothers are key income earners for their families, and Black women are paid 63 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men in the U.S.

“For economic reasons, Holder said, 2020 “was not a good time for Black women to be expanding their families.”

Laura Lindberg, a principal researcher at the pro-choice Guttmacher Institute, also spoke to the disproportionate affect the pandemic has had on women of color. A survey conducted last June by her organization found that more than 40 percent of women had changed their plans about having children due to the coronavirus pandemic, and there were sharp disparities among racial and socioeconomic lines. While 44 percent of Black women and 48 percent of Hispanic women said they wanted to have children later or have fewer children due to the pandemic, just 28 percent of white women responded this way. Lower-income women were also 5 percent more likely than higher-income women to report this change.

Lower-income women and women of color, said Lindberg, were more likely to be essential workers, and “did not have the privilege of staying home during this.” She said they may also have “had school systems which didn’t function as well in terms of providing education and support for families during this time, so the challenges of being a parent and raising children that you already had were greater in these settings.”

Uchida said the pandemic had made her think more about the social safety net in the United States, and what she considers to be a lack of federal support for mothers across the board.

“We’re still in a culture in America where it’s work first,” she said, adding that while some of the benefits to support working mothers in President Joe Biden’s American Families Plan are a step in the right direction, she worries they could quickly fall away should a Republican be elected to the White House in 2024.

Declining birth rates may not constitute a ‘crisis,’ but women still face tough choices

As birth rates in the U.S. have continued to drop in recent years, some economists and demographers have sounded the alarm about the impact that a shrinking population could have on the economy.

In a March interview with CBS This Morning, University of Southern California professor Dowell Myers, who studies demographic trends, called the decline in the U.S. a “crisis,” and expressed fear that at the current rate, there won’t be enough Americans in the workforce to support the elderly population in the future. The Census Bureau has projected that by 2034, Americans 65 and older will outnumber children for the first time in history, raising concerns about how Social Security and retirement benefits will be financed.

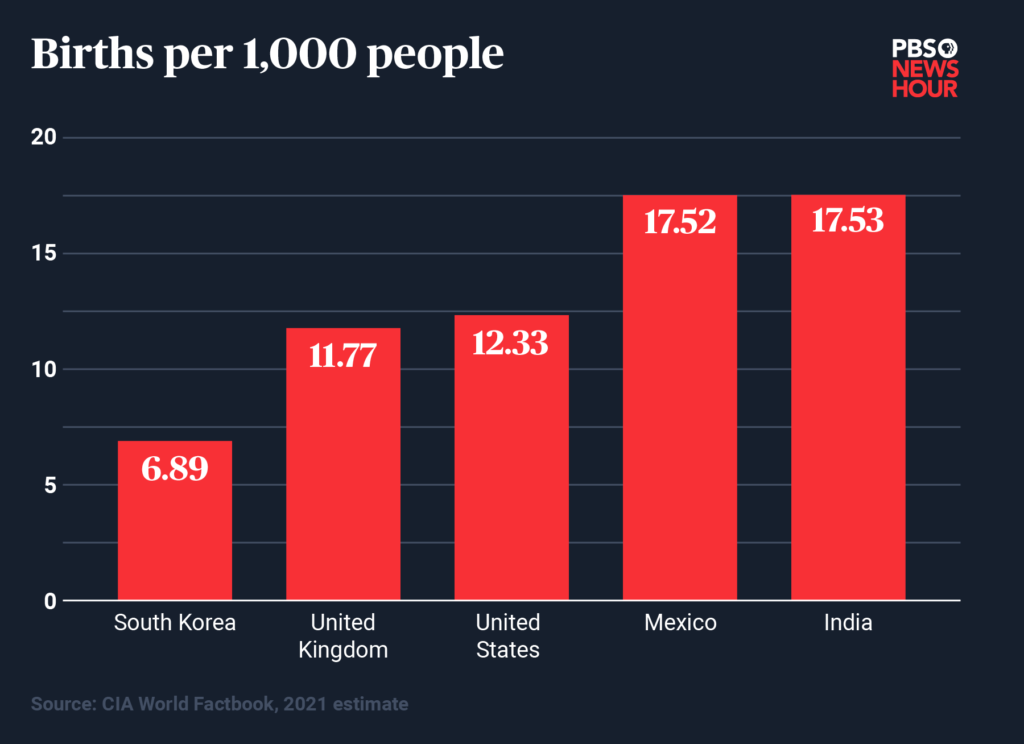

A 2021 estimate of birth rates by country. Graphic by Megan McGrew.

“You’re starting to talk about a several-year period of hundreds of thousands of fewer children being born,” said Levine, who said this “baby bust” could be as significant as the Baby Boom was in terms of societal impact — albeit for different reasons.

“These are the individuals who we are relying on to fund our social-security system. Fewer workers contributing means more difficulty paying for benefits of current retirees. In some sense, changes like this have implications on society for decades,” Levine said.

But the Guttmacher Institute’s Lindberg cautioned that declining birth rates should not solely be viewed as a negative phenomenon, particularly as teen pregnancies in the U.S. have dropped significantly in recent years and access to birth control has improved.

“A large part of this decline has been reductions in unintended pregnancy and improvements in women’s ability to control when they get pregnant,” Lindberg said. “Access to free and affordable contraception through shifts in the insurance system have really made it possible for women to better control having children when they want.”

Two mothers who spoke with the PBS NewsHour said they have benefited from having control over their reproductive choices, but still felt that the pandemic threw off their ability to plan for a family.

When Melissa Green, 40, got pregnant through in-vitro fertilization in 2018, she had complications with preeclampsia, a condition usually characterized by high blood pressure. Her daughter was delivered by C-section and spent two weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit before she could go home. While Green had been hoping to get pregnant again during the first half of this year, she worried that her family wouldn’t be able to be with her in the hospital due to ongoing coronavirus restrictions.

“Since my support system is my family and friends, not having any kind of support system in another situation like that was just really not an option,” Green said when discussing her feelings about having another child this year.

“I’m pretty disappointed,” she said. “I wanted to try for my family as soon as possible. I think it would improve my chances of lessening complications, being as young as possible. And I would like my children to be somewhat close in age.”

“There were too many unknowns for us to feel really comfortable bringing a child into the world at that time.”Grace, another woman who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the situation, said she and her husband made the “very difficult decision” to terminate a pregnancy last spring because they were having trouble managing the anxiety of the two kids they already have, and worried the political climate in the country was becoming more fearsome.

“At that point, remember, there were protests in the streets daily and there was a lot of uncertainty about women’s rights, our future,” said the 37-year-old Boston resident. “There were too many unknowns for us to feel really comfortable bringing a child into the world at that time.”

Demographers say we will have to wait and see whether the birth decline represents a delay in women having children, or a fundamental shift in the population. Other developed nations with stronger social safety nets, such as Italy and Japan, have faced similar challenges with fertility rate declines and have not been able to substantively slow the trend.

The 2008 recession, said Lindberg, set us on this path of continued declines in fertility. “So if the pandemic is a shock to the system that brings fertility down even further, does that become the new normal?” she asked. “I think that’s the million dollar question here.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eelsGqu81on6ivXam1pnnCqKmoppGrtrPB0manmqaUmrqqr4yhmKxlk52ur7PEnWStoJVixKLFjJqknqqZmK6vv4ytn6Kmm2Kuo7vUrWSpqpWcu6K6wrI%3D